The Friend-Enemy Distinction

The Results of Domestic Infighting without an Enemy

VIEWPOINT

Conflict Dispatch

7/16/20255 min read

Carl Schmitt, a controversial German political theorist influential in international relations, proposed that politics can be reduced to a single principle: the distinction between friend and enemy. For Schmitt, the friend-enemy distinction is not based on morality, ideology, or economics but on identifying an enemy posing an existential threat in military, cultural, or political terms. Schmitt mentions various potential consequences if the friend–enemy distinction breaks down:

1. Depoliticization and Neutralization Loss of Political Purpose: Carl Schmitt believed politics hinges on clearly defining friends and enemies in existential terms. Without this distinction, politics is reduced to mere management, economics, morality, or aesthetics, losing its true essence. Neutralization of Conflict: Efforts to erase or neutralize the friend-enemy distinction don't solve real issues but instead bury genuine conflicts beneath artificial harmony, creating a superficial unity without resolving underlying tensions.

2. Internal Fragmentation and Societal Disintegration Collapse of Collective Identity: When societies lack a clear external enemy or coherent sense of friendship, they struggle to define who they are. This ambiguity fosters internal divisions, eroding political unity. Rise of Internal Conflicts: If the external threat disappears or becomes unclear, internal groups turn on each other, perceiving fellow citizens as existential threats. This internal hostility can lead to civil unrest or even civil war.

3. Loss of Sovereignty and Decisiveness Inability to Act Decisively: Schmitt argues politics demands decisive action, especially when existential threats emerge. Without a clear friend-enemy distinction, states become paralyzed, incapable of decisive responses during crises. Vulnerability in Crisis: Failing to identify enemies clearly means a state can't effectively defend itself or mobilize against external threats, potentially leading to defeat, subordination, or even destruction of the political order.

4. Domination by External Powers or Ideologies Exposure to External Influence: A society that refuses or fails to clearly define its enemies becomes vulnerable to external manipulation or domination. Schmitt views this openness as a direct route to political subjugation. Universalist Ideologies Replace Real Politics: Schmitt harshly criticizes universalist ideals, like humanitarianism and moral universalism, as they blur genuine political realities. Such abstract ideologies mask real interests, causing societies to overlook genuine threats and embrace (foreign) vague, utopian ideals.

5. Emergence of a False, Apolitical Consensus Illusion of Unity: Societies neglecting the friend-enemy distinction create a false consensus of actively ignoring real threats, leading to a fragile illusion of harmony easily shattered by real conflicts. Rise of Technocratic Governance: With politics sidelined, society shifts toward technocratic and bureaucratic management. Schmitt sees this depersonalized rule as incapable of effectively addressing true political crises.

6. Existential Danger to the Political Community Risk of Annihilation: Ultimately, Schmitt emphasizes the existential danger posed by losing the friend-enemy distinction. Without clearly defined threats, political communities risk annihilation, losing their identity, independence, and reason to exist.

We will now take a look at the state of the US and the collective West.

1991: The Soviet Union had just collapsed, and there were no other countries capable of rivaling the US in any meaningful way. The 1990s and 2000s marked the era of a unipolar world order, in which the US, and the West more broadly, achieved incredible power.

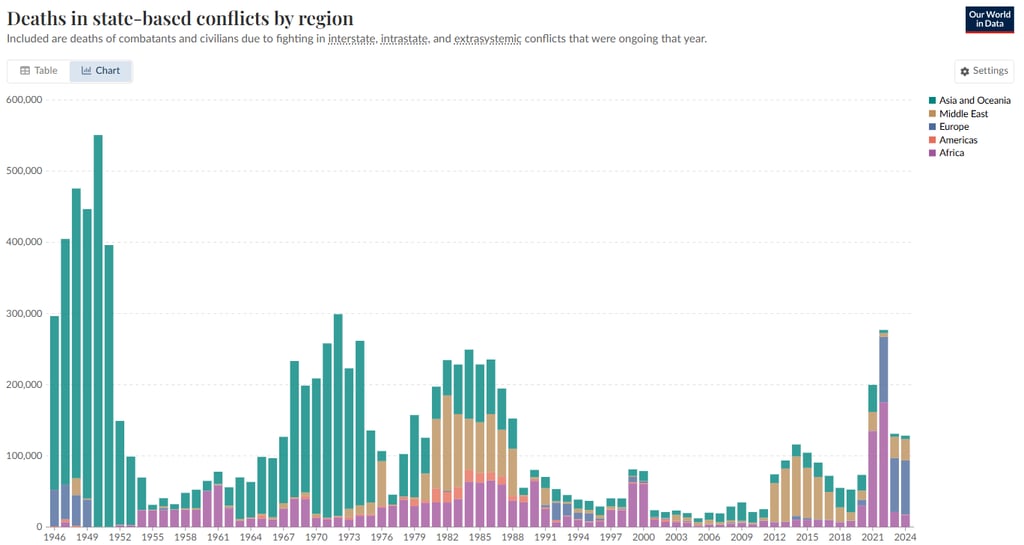

The US managed to leverage its position in international organizations to project power and influence across the world, often avoiding war. Despite claims by contemporary anti-Western scholars and thinkers that the US wreaked havoc on the world during this period without any checks or controls, research shows that the unipolar world order was the most peaceful form of “polarity” in recent times compared to bi- and multipolar world orders.

In 2025, looking back, a key question emerges: what went wrong? How did the United States lose its hegemonic status, ending the unipolar world order? Did wars play a decisive role? And why is Schmitt's theory relevant to the dwindling influence of the West, especially the US?

After 1991, the West failed to adapt and apply the friend–enemy distinction in a meaningful way. While small regimes were toppled, such as Yugoslavia, they already were remnants of the past.

After 9/11, the GWOT created a new friend–enemy distinction, mainly in the US. The new enemies were Islamists in the Middle East and the regimes harboring or supporting them, directly or indirectly. However, while the enemy was identified, the friends of the US were skeptical.

From the outset, many Europeans did not view Middle Eastern Islamists as an existential threat—militarily, culturally, or politically. Western unity in supporting interventions like those in Iraq and Afghanistan faltered, and these campaigns became unsustainable amid growing public demoralization. (We could now talk in depth about the GWOT, questionable practices used to justify the interventions, and so on, but that’s not the topic of this article.)

The enemy was no longer seen as worth fighting and was no longer perceived as a threat. Therefore, there was no enemy anymore.

These developments came with the resurgence of US isolationism, initiated by the Obama administrations and continued through both Trump administrations. The promise: never again would the population be drawn into confusing and opaque wars with no clear or questionable end goals.

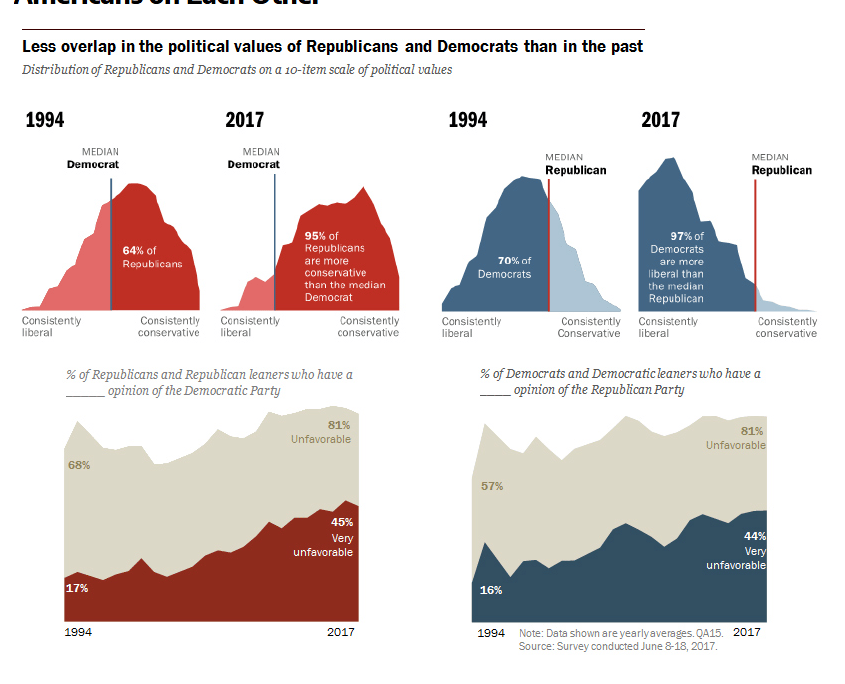

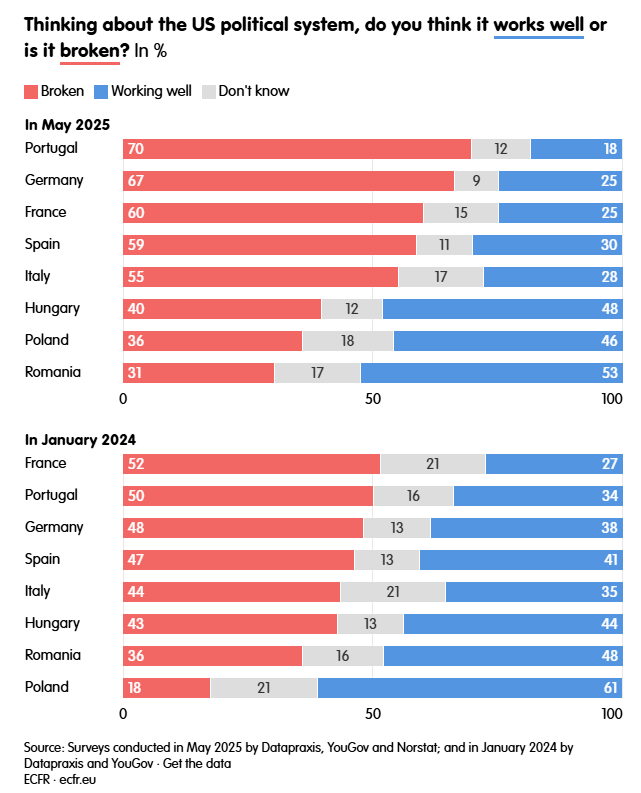

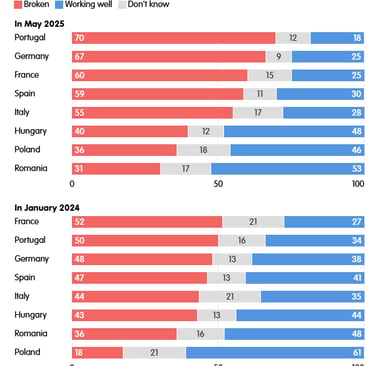

With Islamists no longer existing as a defined enemy, the US almost instantly turned inward, experiencing polarization, fragmentation, and aversion toward the notion of a "strong USA," which had become associated with the widely hated GWOT.

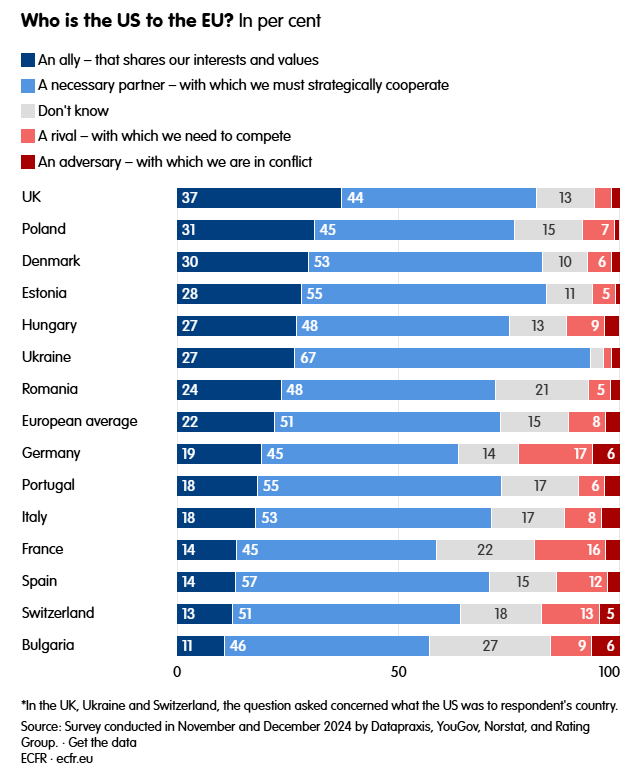

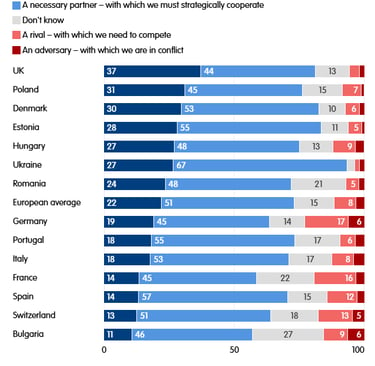

The US isn’t just harming itself. It could also drag down the broader collective West with it. Europeans are increasingly pessimistic about transatlantic relations and the internal state of the United States. Most now see the US not as a close ally that shares their interests and values, but merely as a necessary partner.

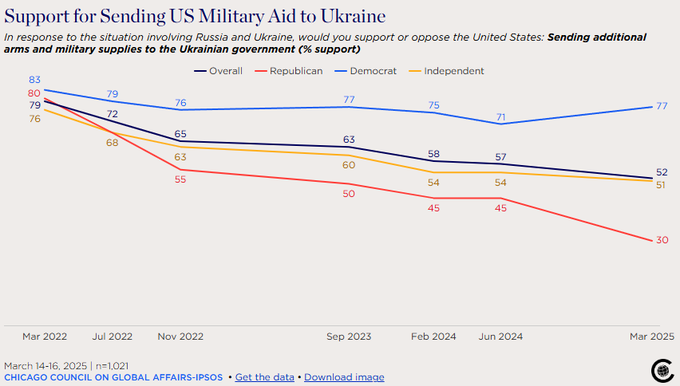

There are also deep divisions within the US regarding military aid to Ukraine. While some opposition may stem from the narrative of the US funding "forever proxy wars," another reason is the inability to define a common enemy.

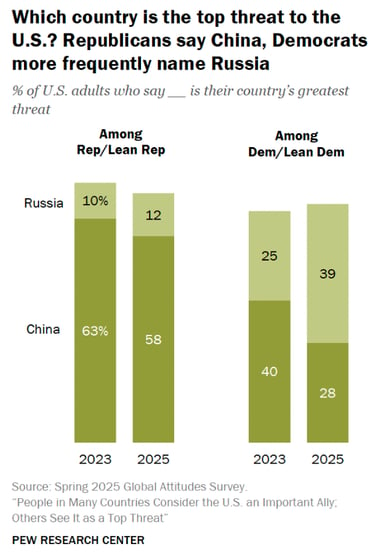

Americans struggle to agree on whether Russia or China poses the greater threat. While Republicans overwhelmingly cite China, most Democrats name Russia. Result: The friend-enemy distinction is not possible.

If the United States does not clearly identify its allies and its enemies, foreign policy issues will continue to spiral out of control, and the US will soon lose its hegemonic status. Without strong alliances, a weakened United States will not experience a "Golden Age."

“The specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy. A people that no longer can make the distinction between friend and enemy ceases to exist politically.”

- Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political